We have seen how to solve first-order differential equations of the form \begin{equation} \dv{v}{t} = f(v) \qquad\text{or}\qquad \dv{x}{t} = g(x) \label{eq:firstorder} \end{equation}

However, Newton’s equations of motion (in one dimension) are typically second-order

differential equations of the form \(m \dv[2]{x}{t} = F(x, v, t)\) where

\(v = \dv{x}{t}\) and \(F\) is some function of the position, velocity, and time. We have seen how

we can use Euler’s method to develop an approximate numerical solution to a first-order

equation, where we use the fact that we know the function that computes the derivative,

and we can use small but finite steps to estimate the true solution. We have also seen

that nifty functions like solve_ivp can use higher-order numerical methods to compute

much more accurate solutions to first-order equations without having to take really tiny

steps. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could somehow take advantage of these tools to solve

second-order differential equations?

As it turns out, we can leverage all we have learned about integrating first-order equations to handle second-order equations! The trick is to express the single second-order equation as two coupled first-order equations and to solve them simultaneously.

Let’s see how that can work using a particularly simple example. Suppose we wish to solve \begin{equation}\label{eq:SHODE} m\ddot{x} = - k x \end{equation} which describes a particle of mass \(m\) subject to a restoring force that grows linearly with displacement from \(x = 0\). (Remember that the dots signify derivatives with respect to time.)

If we use more conventional notation, in which \(\dot{x} = v\) and \(\ddot{x} = \dot{v}\), we could write \begin{align} \dot{v} &= - \frac{k}{m} x \\ \dot{x} &= v \end{align} each of which is a first-order equation. That is, by introducing \(v = \dot{x}\) as a “new dependent variable”, we can break apart the single second-order equation into two coupled first-order equations. Easy!

Let’s say that again. To solve a second-order differential equation of the form

\begin{equation} \ddot{x} = f(x, \dot{x}, t) \end{equation}

use two dependent variables, \(x(t)\) and \(v(t)\), to write the coupled equations \begin{equation}\label{eq:blah} \dv{}{t} \begin{bmatrix} x(t) \\ v(t) \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v \\ f(x, v, t) \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}

then we can use Euler’s method—or the better methods of solve_ivp —to solve

simultaneously for \(x(t)\) and \(v(t)\).

Recall that the call signature of

solve_ivp is solve_ivp(deriv_func, time_range, initial_values, ...).

Fortunately, the deriv_func can return an array of derivatives, and the

initial_values can be a corresponding array of the initial values of the

dependent variables. Let’s see how the example plays out.

# First prepare the notebook by loading the necessary modules

%matplotlib widget

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import solve_ivp

We have to define a function that computes the vector of derivatives at time \(t\) and a vector of the dependent variables (coordinates), \(Y = [x, v]\). We can list the coordinates in any order we like, as long as use the same order for the derivatives, \([\dot{x}, \dot{v}]\).

def SHOderivs(t, Y, k, m):

"""

Compute the derivatives of a simple harmonic oscillator of mass m and spring

constant k where the dependent variable Y holds [x, v].

"""

x, v = Y # we use x = Y[0] and v = Y[1]

# the derivative dx/dt = v, and

# the derivative dv/dt = -k/m * x

# we have to return the derivatives in the same order as the coordinates

# were delivered in Y

derivs = np.array([v, -k/m * x])

return derivs

Note again that this function receives the coordinates [x, v] in a list (array)

in the variable Y, so it returns the derivatives [v, a]. We can now integrate

the differential equation for the time range \(0 \le t \le 1\), starting with

\(x(0) = 1\) and \(v(0) = 0\).

res = solve_ivp(SHOderivs, [0, 1], [1.0, 0.0],

t_eval=np.linspace(0, 1, 21), args=(4, 0.25))

res

message: 'The solver successfully reached the end of the integration interval.'

nfev: 56

njev: 0

nlu: 0

sol: None

status: 0

success: True

t: array([0. , 0.05, 0.1 , 0.15, 0.2 , 0.25, 0.3 , 0.35, 0.4 , 0.45, 0.5 ,

0.55, 0.6 , 0.65, 0.7 , 0.75, 0.8 , 0.85, 0.9 , 0.95, 1. ])

t_events: None

y: array([[ 1. , 0.98006663, 0.92107572, 0.825395 , 0.6967433 ,

0.54024223, 0.36225911, 0.16986033, -0.02929309, -0.22738616,

-0.41646995, -0.58889897, -0.73787313, -0.85727112, -0.94240378,

-0.9900373 , -0.99845565, -0.96702272, -0.89675673, -0.79050156,

-0.65289549],

[ 0. , -0.79467787, -1.55781879, -2.25895497, -2.86969046,

-3.36596441, -3.72862823, -3.94317039, -3.99972153, -3.89581286,

-3.63647339, -3.23315991, -2.7011724 , -2.06107624, -1.33812055,

-0.56208386, 0.23632515, 1.02504019, 1.77273867, 2.45002813,

3.0295073 ]])

y_events: None

Looking at the output of solve_ivp, we see that the array returned as y is

now two-dimensional, since our coordinate “vector” consists of Y = [x, v]. Let’s make a plot of the solution.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

t = res.t

x = res.y[0,:]

v = res.y[1,:]

ax.plot(t, x, 'ro', label="$x$")

ax.plot(t, v, 'bo', label="$v$")

ax.legend()

ax.set_xlabel('$t$');

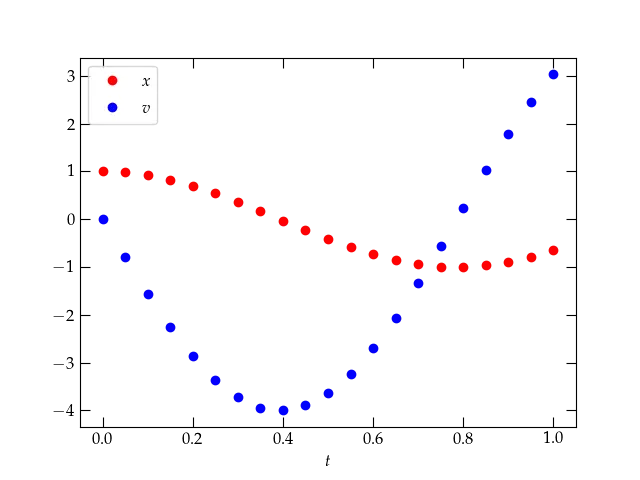

Figure 1 — The solution to Eq. \eqref{eq:SHODE} provided by solve_ivp.

This plot looks very promising. It looks like the start of an oscillation, which you might expect for a mass suspended from a spring. After all, the differential equation we’re solving is

\begin{equation} \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = - \frac{k}{m} x \end{equation}

which simplifes to

\begin{equation} \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = - 16 x \end{equation}

for the particular values of \(k = 4\) and \(m = 1/4\) that we used in our solution. As you can readily verify, the function

\begin{equation} x = \cos(4t) \end{equation}

solves this equation. Furthermore, its derivative vanishes at \(t = 0\), as we require. Let’s add this function to the plot to see how the numerical solution is doing.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

t = res.t

x = res.y[0,:]

ax.plot(t, x, 'ro', label="$x$")

tvals = np.linspace(0, 1, 51)

xvals = np.cos(4 * tvals)

ax.plot(tvals, xvals, 'g-', label=r"$x_{\mathrm{true}}$")

ax.legend()

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.set_ylabel('$x$');

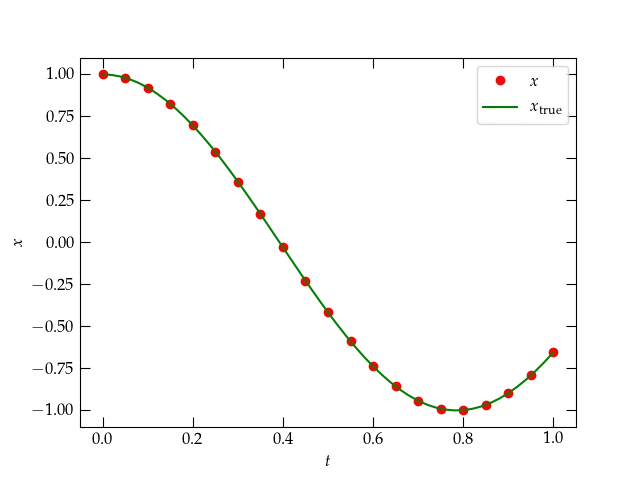

Figure 2 — Comparison of the numerical solution to the SHO differential equation (red dots) to the analytic solution (green curve).

That agreement between the theoretical curve and the numerical solution looks very good, but we

expect that there will be some errors in the numerical solution. Make a plot of the errors for

both \(x\) and \(v\). How small do you have to make rtol to produce an “acceptable” level of error,

in your opinion?

So far, we have asked solve_ivp to produce a solution at specific values of

the independent variable \(t\), which we specify by the keyword parameter

t_eval set to a list or array of values. It can be useful, however, not to

have to specify the particular values at the start, but to have solve_ivp

return a smooth function. We can manage this by asking for

dense_output=True. Let’s see how this works.

res = solve_ivp(SHOderivs, [0, 1], [1.0, 0.0], dense_output=True, args=(4, 0.25))

res

message: 'The solver successfully reached the end of the integration interval.'

nfev: 56

njev: 0

nlu: 0

sol: <scipy.integrate._ivp.common.OdeSolution object at 0x137e455e0>

status: 0

success: True

t: array([0.00000000e+00, 6.24375624e-05, 6.86813187e-04, 6.93056943e-03,

6.93681319e-02, 2.63647530e-01, 5.07499921e-01, 7.37486428e-01,

9.86950372e-01, 1.00000000e+00])

t_events: None

y: array([[ 1.00000000e+00, 9.99999969e-01, 9.99996226e-01,

9.99615762e-01, 9.61750781e-01, 4.93512971e-01,

-4.43557322e-01, -9.81750147e-01, -6.91522218e-01,

-6.52895491e-01],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -9.99000989e-04, -1.09889972e-02,

-1.10874908e-01, -1.09570295e+00, -3.47885073e+00,

-3.58484295e+00, -7.59559602e-01, 2.88912221e+00,

3.02950730e+00]])

y_events: None

Notice that the output now includes an OdeSolution object in res.sol. We can

use it to evaluate the solution at a point in time within the range we have

simulated as follows:

res.sol(0.5)

array([-0.41646995, -3.63647339])

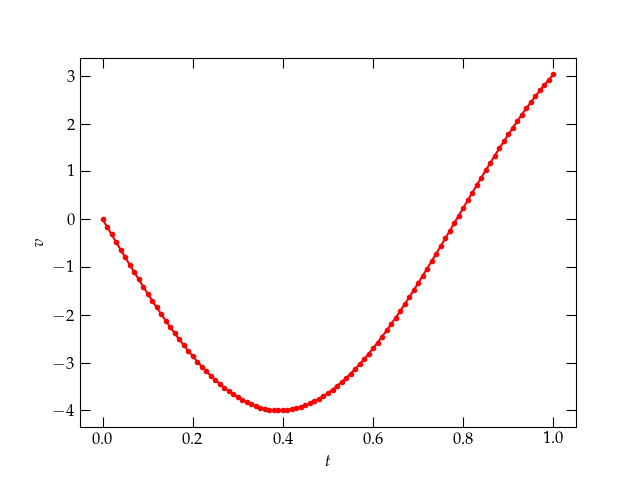

The solution returns an array (vector) of values of the dependent variables \([x, v]\). Here’s how we can use the solution to make a nice smooth plot of the results. We’ll plot the velocity:

tvals = np.linspace(0, 1, 101)

Xvals = res.sol(tvals)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(tvals, Xvals[1,:], 'r.-', label=r'$v$')

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.set_ylabel('$v$');

Figure 3 — Plotting the output of solve_ivp.

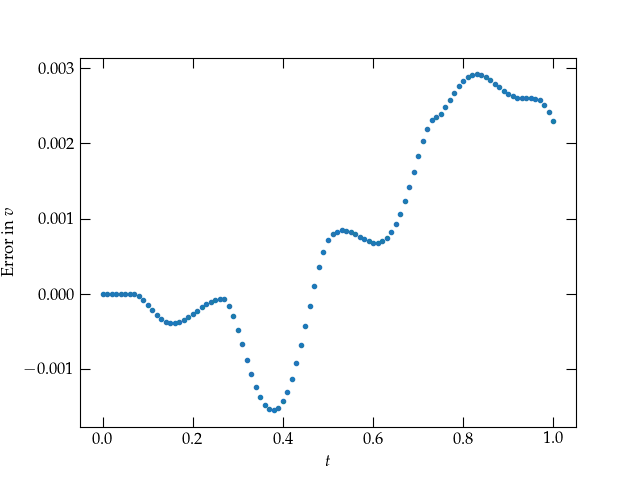

Let’s see what the error in the velocity looks like:

errors = Xvals[1,:] + 4 * np.sin(tvals * 4)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(tvals, errors, '.')

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.set_ylabel('Error in $v$');

Figure 4 — Error in the computed velocity from solve_ivp.

Now, choose a (set of) differential equation(s) to integrate and write a function that takes in a vector of coordinates and returns the derivatives of those coordinates. Suggestions for systems you could use:

A damped simple harmonic oscillator: \(\ddot{x} = -\frac{k}{m} x - \frac{b}{m} \dot{x}\), which has analytic solution \(x(t) = \left(x_0 \cos \omega_1 t + \frac{v_0 + \beta x_0}{\omega_1} \sin\omega_1 t\right) e^{-\beta t}\) for \(\beta = 2b/m\), \(\omega_0 = \sqrt{k/m}\), and \(\omega_1 = \sqrt{\omega_0^2 - \beta^2}\). Use coordinates \([x, v]\), and the derivatives \([v, -\omega_0^2 x - \beta v]\) for \(\omega_0 = \sqrt{k/m}\).

A projectile subject to linear drag: \(\ddot{x} = -g - \frac{b}{m} \dot{x}\) which has the solution \(x(t) = x_0 - v_T\left(t + \frac{e^{-\beta t}}{\beta} \right) + \frac{v_0}{\beta}(1 - e^{-\beta t})\) where \(\beta = b/m\) and the terminal velocity is \(v_T = m g / b = g / \beta\). Use coordinates \([x, v]\) and the derivatives \([v, -g - \frac{b}{m} v]\).

plt.polar(θ, r) to make polar

plots of the trajectories.Then call solve_ivp with your function and see how well it does. Investigate

how the error depends on the method and/or the tolerances (rtol or

atol). Use a log-log plot for the absolute value of the error.

The step to handling more than one variable is now very small. For each second derivative, we use two variables, one for the coordinate and one for its first derivative, to get the coupled equations \begin{equation} \begin{bmatrix} \dot{x}_1 \\ \dot{v}_1 \\ \dot{x}_2 \\ \dot{v}_2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v_1 \\ \ddot{x}_1 = f_1(t, x_1, v_1, x_2, v_2) \\ v_2 \\ \ddot{x}_2 = f_2(t, x_1, v_1, x_2, v_2) \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}

Then we pack all these dependent variables in a single array Y and supply a

function that computes each one’s derivatives like so:

def bigderivs(t, Y, *other_parameters):

x1, v1, x2, v2 = Y # break apart the individual variables, for convenience

a1 = ... # compute the acceleration of coordinate 1

a2 = ... # compute the acceleration of coordinate 2

return np.array([v1, a1, v2, a2]) # return the vector of derivatives

The argument other_parameters is a list of any additional parameters that our

function may require to evaluate the derivatives. When you precede a variable

name with an asterisk, it means that the variable holds a (possibly empty)

list. (When you precede a variable name with a double asterisk, the variable

holds a dictionary of key-value pairs. It’s the way optional keyword arguments

may be passed to a function.)

A conical pendulum is a point mass suspended by a rigid rod that is held fixed at a frictionless pivot. Before we attempt a general solution for arbitrarily large angles with respect to the vertical, we could attempt a solution valid for small angles. Let’s use a cartesian coordinate system with \(z\) pointing up, so the \(x\)-\(y\) plane is horizontal. For a pendulum of length \(\ell\), it is possible to show that in the case of small displacements from equilibrium, the accelerations in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions are given by

\begin{align} \ddot{x} &= -\frac{g}{\ell} x \\ \ddot{y} &= -\frac{g}{\ell} y \end{align}

Write a function that computes the derivatives for such a conical pendulum in the small-amplitude limit and investigate the behavior of the solution for different initial conditions.

To handle angles that are not small, it is more convenient to use spherical polar angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) and to employ Lagrangian mechanics, which develops the equations of motion from energy, rather than forces. We will discuss this approach soon in more detail, as it can be very helpful for certain projects. In the meantime, the summary is the following:

In this case, the potential energy is \begin{equation}\label{eq:U} U = - m g \ell \cos\theta \end{equation} if we measure \(\theta\) from the south pole and the kinetic energy is \begin{equation}\label{eq:T} T = \frac12 m \ell^2 ( \dot{\theta}^2 + \sin^2\theta \dot{\phi}^2) \end{equation}

After computing the lagrangian \(L = T-U\) and applying the Euler-Lagrange equation for \(\theta\) and \(\phi\), we get the following equations of motion: \begin{align} \ddot{\theta} &= \sin\theta \cos\theta \dot{\phi}^2 - \frac{g}{l} \sin\theta \label{eq:thd} \\ \ddot{\phi} &= - 2\frac{\dot{\phi}_0 \sin^2 \theta_0}{\sin^3 \theta} \cos\theta \; \dot{\theta} \label{eq:phid} \end{align}

Use these dynamical equations and solve_ivp to compute trajectories in the projection of the pendulum’s position in the \(xy\) plane.

Next: The Quantum SHO