Lines are so simple! Just about the most basic function you can think of. There’s not much to them, right? \(y = mx + b\) and all that. What’s to know? Well, calculus teaches that continuous functions look like lines when you zoom in enough. For small changes, a tangent line approximation may be all you need. If your function has more than one independent variable, then a tangent hyperplane is the obvious generalization. Displacements from the point of tangency are vectors; they are elements of a vector space.

Of course, not everything is linear. Some of the most interesting and challenging phenomena are inherently nonlinear. A friend of mine in graduate school often joked “Linearity breeds contempt!” Then again, he studied hurricanes and the Navier-Stokes equations of fluid dynamics are nonlinear in general.

In essence, linear algebra is the mathematics of objects for which the operations of addition and of multiplication by a scalar are defined. That is, linear algebra is the mathematics of vector spaces.

Let’s start with a physics definition that applies in mechanics and electromagnetism. A vector is a quantity with magnitude and direction in (two- or) three-dimensional space. Examples include position, velocity, acceleration, force, momentum, electric field, magnetic field, etc.

You already know all about such objects. You can add them if they have the same dimensions. You can stretch or shrink them (by multiplying by a scalar). You’ve been using them for years now, although you may still be pretty sloppy about notation (you know, putting that arrow on top!).

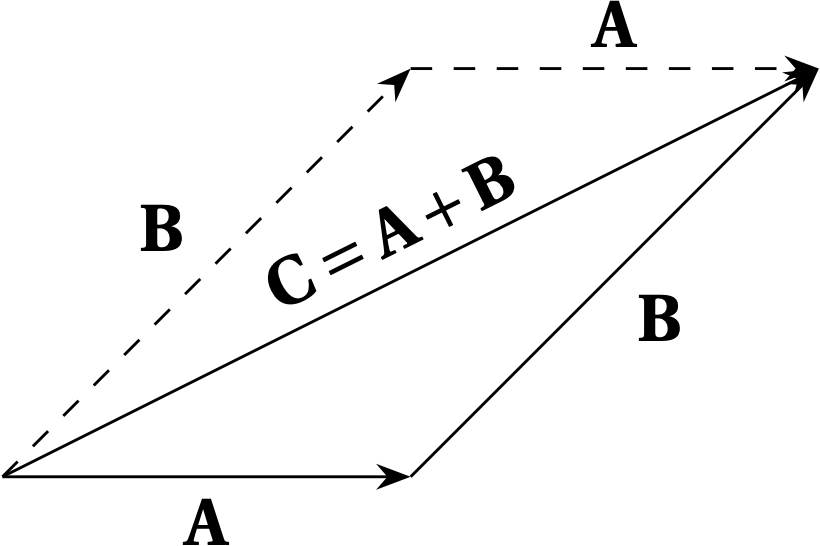

However, having a magnitude and direction is not quite a sufficient definition for a vector, until we supplement with rules for addition and for multiplication by a scalar. If we adopt a geometric approach, then the rule for vector addition is to place the tail of vector \(\vb{B}\) at the head of vector \(\vb{A}\), and draw the arrow from the tail of \(\vb{A}\) to the head of \(\vb{B}\), as illustrated below.

Figure 1 — Addition of vectors: \(\vb{C} = \vb{A} + \vb{B}\). Note that \(\vb{B} + \vb{A}\), shown dashed, yields the same vector \(\vb{C}\). In other words, vector addition is commutative.

Now, I’d like to generalize the notion of a vector as being an element of a vector space governed by the following axioms (vectors are shown in boldface; Greek letters represent scalars):

There are many familiar examples, such as directed line segments in a plane, using the usual parallelogram law of addition, and all the previously mentioned vectorial quantities, but consider the following:

Pick one of these examples and confirm that all ten axioms are satisfied.

Suppose we revise the rule for multiplication of a directed line segment (an arrow) by a scalar to yield the zero vector for all vectors and scalars: \(\alpha \vb{v} = \vb{0}\). This rule violates only one of the ten axioms, making it not a vector space. Which axiom does it violate?

A linear operator \(\hat{A}\) has the following behavior \begin{equation}\label{eq:linear-operator} \hat{A}(\alpha \vb{x} + \beta \vb{y}) = \alpha \hat{A}\vb{x} + \beta \hat{A}\vb{y} \end{equation} In this expression, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are scalar values (either real numbers or complex numbers) and \(\vb{x}\) and \(\vb{y}\) are \(N\)-dimensional vectors. The operator \(\hat{A}\) transforms a vector in an \(N\)-dimensional space into another vector in the same \(N\)-dimensional space. Equation (\ref{eq:linear-operator}) says that you get the same result whether you combine vectors and then transform with the operator as when you transform the vectors separately and then combine the results. Why is this interesting?

Many physical quantities have this property. In classical mechanics, some linear operators are:

Linear operators are fundamental in quantum mechanics. To distinguish a quantum state vector from other physical vectors, such as position or momentum, we use the notation \(\ket{\psi}\) for represent the quantum state \(\psi\). Quantum mechanical linear operators act on a quantum state vector \(\ket{\psi}\) to produce another state vector \(\ket{\varphi}\) in the same vector space over the field of complex numbers.

So far, we have described one way to combine vectors (addition) and another to scale them (scalar multiplication), but we have no notion of combining vectors to yield a scalar. The inner product between two vectors, denoted \(\langle \vb{v}_1, \vb{v}_2 \rangle\), is such a function. If the vector space is over the real numbers (the amplitudes are all real), then the inner product is defined by \begin{equation} \langle \vb{a}, \vb{b} \rangle = \vb{a} \vdot \vb{b} = \sum_{i=1}^N a_i b_i = (a_1, \ldots, a_N) \vdot \begin{pmatrix} b_1 \\ \vdots \\ b_N \end{pmatrix} \label{eq:innerproduct} \end{equation}

The “length” or norm of a vector is given by \begin{equation} || \vb{a} || = \sqrt{\langle \vb{a}, \vb{a} \rangle} = \left( \sum_{i=1}^{N} a_i^2 \right)^{1/2} \label{eq:norm} \end{equation} which is what we would expect from the Pythagorean theorem. (For more information on norms, See this page).

Mathematicians are wont to preserve the “double-pipe” notation for norm, as shown in Eq. (\ref{eq:norm}), to distinguish it from the absolute value of a scalar quantity (either real or complex). Physicists typically adopt a more expansive view; both represent the magnitude or length of either a scalar or vector quantity. Hence, most physicists avoid the “double-pipe” notation and write \(|\vb{a}| = a\).

However, if the vector space is over the field of complex numbers, then the inner product defined in Eq. (\ref{eq:innerproduct}) won’t generally produce a real nonnegative value that can represent the “length” of the vector. In this case, we modify the definition of the inner product by taking the complex conjugate of the first argument: \begin{equation} \langle \vb{a}, \vb{b} \rangle = \sum_{i=1}^N (a_i)^* b_i \end{equation} In matrix notation, this is the product of the conjugate-transpose of column vector \(\vb{a}\) multiplying column vector \(\vb{b}\): \begin{equation} \langle \vb{a}, \vb{b} \rangle = (a_{1}^{*}, a_{2}^{*}, \ldots, a_N^*) \vdot \begin{pmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ \vdots \\ b_N \end{pmatrix} \end{equation} This definition means that the inner product of a vector with itself is positive definite and suitable for defining a magnitude or length of the vector: \begin{equation} \ev{\vb{a}, \vb{a}} = \sum_{i=1}^N (a_i)^{*} a_i = \sum_{i=1}^N |a_i|^2 \ge 0 \end{equation} which means that the length of \(\vb{a}\) is \begin{equation} \boxed{ |\vb{a}| = \sqrt{\ev{\vb{a}, \vb{a}}} = \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^N |a_i|^2 } } \end{equation} Note that this is the same as Eq. (\ref{eq:norm}), apart from the absolute value sign surrounding each (complex) component of the vector.

What is the length of \(\vb{a} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\\ i \\\ -1 \\\ -i \end{pmatrix}\)? If \(\vb{b}^{T} = (1, e^{i\phi}, e^{2i\phi}, e^{3i\phi})\), what is \(\langle \vb{b}, \vb{a} \rangle\)?

If the vector space is over the field of complex numbers, the two vectors of the inner product must be treated differently; the amplitudes of the first vector are conjugated before multiplying by the corresponding amplitudes of the second vector. A pioneer of quantum mechanics, Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac, developed a notation to handle this conjugation for vector spaces over the field of complex numbers that physicists use to this day to represent states in quantum mechanics. In Dirac notation, a vector \(\psi\) is denoted \(\ket{\psi}\) and its conjugate transpose is denoted \(\bra{\psi}\), so that the inner product of \(\psi\) with itself is \(\bra{\psi}\ket{\psi}\) (where we simplify the notation to show only a single bar between the left- and right-hand sides).

In Dirac notation, the vector \(\ket{\psi}\) is called a ket and its dual (conjugate transpose) \(\bra{\psi}\) is called a bra, so that their inner product is a bracket (which was inspired by the Poisson bracket of theoretical mechanics). Every ket vector has its corresponding bra vector, and their inner product yields a nonnegative real number.

Every physically observable quantity (e.g., momentum, angular momentum, position, etc.) corresponds to a special kind of linear operator, called a Hermitian operator, whose properties we will define and explore below. Examples:

If the components of vector \(\ket{a}\) in some basis are \((a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_N)\), then the components of the dual vector \(\bra{a}\) in the same basis are \((a_1^*, a_2^*,\ldots, a_N^*)\). Furthermore, we can represent the ket vector \(\ket{a}\) in this basis as a column vector, \begin{equation} \ket{a} \longrightarrow \pmatrix{a_1 \\ a_2 \\ \vdots \\ a_N} \end{equation} and the “bra” vector (the dual) as a row vector \begin{equation} \bra{a} \longrightarrow \pmatrix{a_1^{*} & a_2^{*} & \cdots & a_N^{*}} \end{equation} so that the inner product is achieved by standard matrix multiplication of bra and ket: \begin{equation} \braket{a}{a} \longrightarrow \pmatrix{a_1^{*} & a_2^{*} & \cdots & a_N^{*}} \vdot \pmatrix{a_1 \\ a_2 \\ \vdots \\ a_N} = \sum_{i=1}^N |a_i|^2 \end{equation} which is a manifestly nonnegative real number.

Two vectors \(\vb{a}\) and \(\vb{b}\) are linearly independent if and only if \begin{equation} \vb{a} \cdot \vb{b} = |\vb{a}| |\vb{b}| \cos\theta_{ab} < |\vb{a}| |\vb{b}| \end{equation} which means that they are not colinear. In general, a vector space of dimension \(D\) is spanned by \(D\) linearly independent vectors, which are often chosen to be unit vectors in each of the Cartesian directions: \(\vb{e}_1 = (1,0,0,\ldots)\), \(\vb{e}_2 = (0, 1, 0, \ldots)\), etc.

The inner product described above takes two vectors of equal dimension and contracts them to produce a scalar. In matrix language, it is the product of the transpose of the first vector (converting a column vector to a row vector) by the second. What happens if we let the first vector remain a column vector but “contract” it with the transpose of the second vector? That is, take \[ \mat{M} = \begin{pmatrix} a_1 \\ a_2 \\ \vdots \\ a_m \end{pmatrix} \vdot \begin{pmatrix} b_1 & b_2 & \cdots & b_n \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_1 b_1 & a_1 b_2 & \cdots & a_1 b_n \\ a_2 b_1 & a_2 b_2 & \cdots & a_2 b_n \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_m b_1 & a_m b_2 & \cdots & a_m b_n \end{pmatrix} \] This is called the outer product of the two vectors and produces a rectangular matrix with \(m\) rows and \(n\) columns, where \(m\) is the dimension of \(\vb{a}\) and \(n\) is the dimension of \(\vb{b}\).

There are two primary problems in linear algebra. The first is to solve for \(\vb{x}\) in equations of the form \begin{equation} \mat{A} \vdot \vb{x} = \vb{b} \end{equation} for known matrix \(\mat{A}\) and vector \(\vb{b}\). You undoubtedly know how this can be accomplished, in principle, using Gauss-Jordan elimination to compute the inverse of \(\mat{A}\) so that \(\vb{x} = \mat{A}^{-1}\vdot\vb{b}\). For small matrices, this is straightforward; with large matrices it may be a poor strategy and require considerably more computation than needed. When \(\mat{A}\) is known to have certain properties (it may be symmetric, or tridiagonal, or Hermitian, or …), there are specialized algorithms that speed up the computation (and may avoid numerical roundoff issues that may spoil the solution developed by a generic algorithm). We will explore some strategies for factoring \(\mat{A}\) into the product of two or three matrices with special forms (such as upper- or lower-triangular, diagonal, etc.) that allow efficient solution for \(\vb{x}\).

The second is to find the solutions to \begin{equation} \label{eq:eigenvector} \mat{A} \vdot \vb{x} = \lambda \vb{x} \end{equation} Such solutions \(\vb{x}\) are called eigenvectors and the corresponding values of \(\lambda\) are the eigenvalues. Because Eq. (\ref{eq:eigenvector}) is homogeneous in \(\vb{x}\), eigenvectors may be arbitrarily scaled. However, eigenvalues \(\lambda\) are uniquely determined by the matrix \(\mat{A}\).

Next: Norms